Updated September 20, 2022

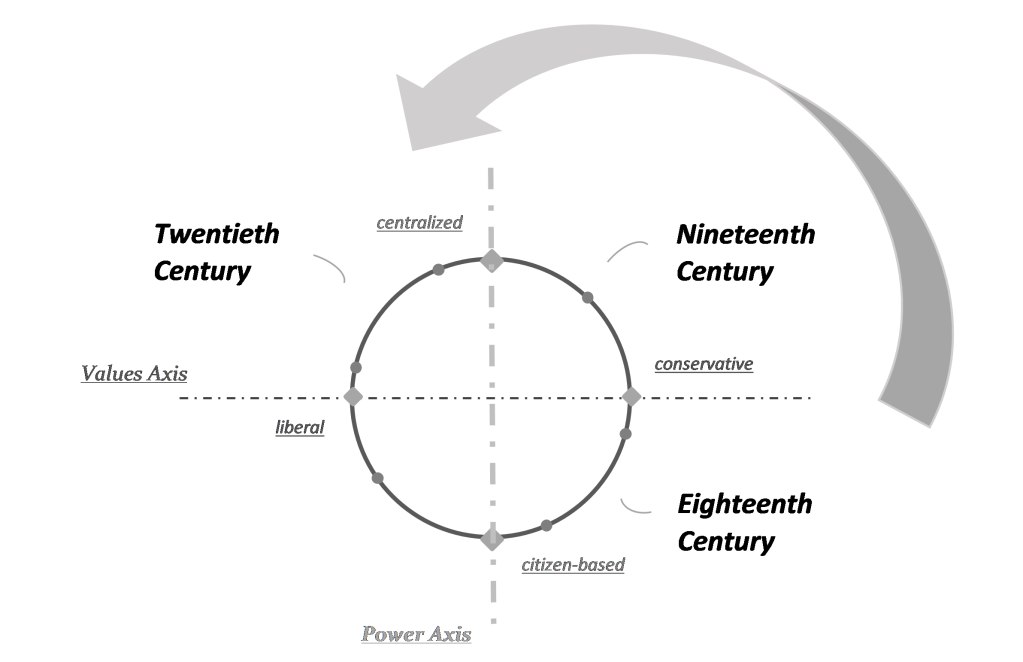

Americans favored local, horizontal, and decentralized organizations from the time of the earliest European settlements, in the early 1600s, through the late colonial era near the end of the 1700s. As a Christian culture with an entrenched warrior ethos, the colonists’ approach to society’s two fundamental questions placed them in the lower right quadrant of the political circle. They were conservatives who favored citizen-based power, much like our time’s recently-deceased Tea Party. The distribution of positions looked something like this ……

Their chosen set of answers placed the new society in conflict with the British government’s authoritarian controls. In one of history’s many ironies, however, the ensuing revolution began to push America’s political outlook upward on the circle, toward that of its adversary.

Alexander Hamilton was Patient Zero in this shift. Wartime experiences on General Washington’s staff convinced him that some form of concentrated control would be required in the nation’s affairs, leading him to argue for a strong central authority at the Constitutional Convention. He then helped to embed that approach in the nation‘s new laws as America’s first Treasury Secretary.

Therefore, in the early 1800s, the country’s collective power answer slowly began to shift from citizen-centric to centralist within the still-conservative, still-Christian, and still-capitalist nation. This trend accelerated during the upheavals of the Civil War, then reached critical mass as new corporations like Standard Oil, US Steel, the railroads, and the House of Morgan drove the late-nineteenth century economy. America held to the same values as in earlier times – paternal, competitive, and God-fearing – but a new power answer was now dominant. Control had become concentrated.

Populist uprisings led to a backlash against the moguls’ grip on the economy, however. But, in yet another irony, the citizens did not take back the initiative. Instead, a Stockholm Syndrome solution was established: the central government was made much more musculature and robust. In this way of thinking, “if you’re up against a giant, find an even bigger giant to represent your interests.” And then hope it actually follows through in representing you.

This change has traditionally (and inaccurately) been viewed as a shift of power, with control moving from corporations to the institutions of “federal” agencies. And it continues to be viewed, by a majority of America’s dwindling progressives, as the best hope of representing “the common citizen’s” interests, despite today’s oligarchic behavior to the contrary. Those idealists have the right to believe that an assertive government will protect them, however deluded that might now seem. But it would be incorrect to claim that the nature of power changed with the shift from corporate to governmental authority. Control remained where it had been – within a small group of players in control of top down structures.

In reality, the late 1800s initiated a shift in the values outlook of those who held power, not in the exercise of power itself. A profit-driven attitude toward capital was replaced with standards that were allegedly more community-minded. The core components of this shift were put in place by 1913, with the creation of Federal Reserve, the popular election of U.S. Senators, and the income tax. Control remained concentrated. But Washington DC was now in charge.

The centralizing trend continued under its new leaders, as figures like Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt established new bureaucracies and regulations. Their presidential progeny then consolidated those gains as more authority was ceded to the growing administrative state.

Thus, the twentieth century became a golden age for the upper left quadrant. Power remained centralized, but the liberal values of cooperation, consensus, civil rights, and care for the commons gradually superseded the capitalistic conquests of America’s early industrial age.

A counterclockwise movement around the political circle can thus be discerned across a span of more than three hundred years. The eighteenth century favored the lower right quadrant. The nineteenth featured a shift to the upper right. And by the twentieth, the upper left was in control.

Which brings this post to the key question of our era. What does this movement across time tell us about the twenty-first century? Does past function as prologue?

The multi-generational trend has featured a sequential movement of the country’s center of gravity across three quadrants. If that trend continues, another shift of positions on the circle can be expected. This time, a citizen-empowered liberalism would define the next epoch’s zeitgeist. Liberal values would remain dominant, but America’s exercise of power would become more decentralized. Horizontal, emergent, self-organizing, and often-temporary structures would provide leadership and set policy. The lower left quadrant would rise ……

Two questions come to the fore under this scenario. First, what would the next version of American society look like with the lower left quadrant taking the lead? Second, how would the transition take place?

Characteristics of the New Paradigm

The lower left quadrant was largely depopulated throughout the twentieth century because progressive liberals believed a strong central government would protect the average American. But today, with incomes rising sharply in the DC metro, and the middle class shrinking everywhere else, emerging signs of virulence in a citizen-empowering liberalism are now visible. Grassroots trends like permaculture, functional medicine, and local sourcing find a home in this part of the circle. Related movements like vaccination choice, new urbanism, and homeschooling span the axis between lower quadrants. Stridently independent left-leaning voices continue to gain traction.

Under this new form of liberalism, the nation’s value structure would largely stay the same: issues like environmentalism, women’s ascendancy, and LGBT rights would remain priorities.

In contrast, difficult dislocations would occur in the pragmatic arrangements of American life. Large bureaucracies, both public and commercial, would scale down, implode, or be targeted for elimination. Entertainment and media conglomerates would fall from favor. The federal government’s control and funding would diminish. Wall Street’s financial institutions would retrench.

These losses would be offset by the growing influence of asymmetrically structured local communities. Free speech and transparency would be prioritized. Psychedelics usage would be legitimized, and possibly ceremonialized: an Age of Ayahuasca. The War on Drugs would suddenly seem provincial and Victorian. “Just Say Yes” would govern.

A myriad of new organizations with diverse yet strangely parallel goals would emerge, featuring horizontal and fluid connections between the members and their groups. The community would come first, with the actual definition of “community” being constantly reevaluated. Let’s not be naive, though: this process would feature very few kumbaya moments. Instead, a Darwinian survival-of-the-fittest paradigm would emerge, with most new ideas and structures of self-governance suffering ugly deaths in the country’s desperate pursuit of a more perfect union.

The shift of positional distribution toward the lower left would also impact the other quadrants in ways they have not yet fathomed. For example, the lower right would benefit because the upper left’s diminished influence would reduce the constant threat of Nanny State interventions. Similarly, conservative evangelicals would move lower on the circle, calculating that an alliance with the now-dominant lower left quadrant would protect their religious freedoms. Or, perhaps, they would simply congregate in local communities where they stand a better chance of self-defense.

In contrast, centralist conservatives would fare poorly, due to a simple rule of political geometry: when one quadrant gains power, its diametric adversary loses power. Thus, legacy corporations would languish, American military influence would decline, and the dollar would relinquish its reserve currency status, among other limitations.

The remaining quadrant – the upper left – has the most to lose from a coming shift of influence. The long running heavyweight champion would be shocked to lose her title belt to an upstart contender. Queen of the hill one day. Just another player in the game the next. This loss of status would inevitably lead to the other major question ……

What Would a Transition Period to Lower Left Dominance Look Like?

Would the process of quadrant change be organized and strategic? Or would it be disorderly? Might it begin with some kind of loose structure and then morph into chaos? Or vice versa?

If the path were incremental, the lower left would have to begin by building strong coalitions within the quadrant. Alliances would also have to be built between its two neighboring quadrants.

Initial indications of an internal coalition are emerging in the “heterodox wing” of liberalism, a loose aggregation of free thinking, determined intellectuals. Similarly, nascent alliances between lower left and lower right can be seen in the diverse membership of informal groups like the IDW and Substack Nation.

But after two centuries of holding the reins, centralists of the left and right would be unwilling to relinquish their grip on power. This is especially true of the upper left, which has already utilized unprecedented tactics to maintain control. An oligarchic Republican-Democrat alliance would attempt to stifle the lower left’s growing influence.

This alliance would be resisted by a different kind of left-right coalition: one formed at the bottom of the circle. The resulting vertically-oriented conflict would be intense but would likely be of limited duration. It could turn kinetic, or it could remain cold.

Under a different scenario, though, those carefully constructed alliances and coalitions would be bypassed. Instead, a runaway train of fiscal, financial, and cultural dysfunction could create a cascading series of uncontrolled events. In this story, citizens would have to band into hastily constructed, locally cooperative communities just to survive. Whether for the short-term, or for the longer-term, we would all live in a World Made By Hand.

And of course – unfortunately – the top-of-circle coalition could temporarily halt the flow of history, by maintaining control in some sort of Stalinesque Hunger Games scenario.

Any of the above scenarios could come to fruition, with the most likely outcome being the one none of us can yet imagine. It is our fate as humans that transition scenarios are impossible to foresee in advance. No one can predict the future. Nevertheless, we must insist on looking for patterns and projecting them forward. It is the only method that allows for reasoned preparation.

Relationships between quadrants do seem to follow a predictable structure, though. A counterclockwise movement around the political spectrum has remained uninterrupted since the continent’s first European settlements were established. And it points to an upcoming shift of power downward on the circle.

If the lower left quadrant does gain influence, every other part of the circle, and every participant within them, will be forced to adjust.

Those adjustments will be difficult for most and non-survivable by some. But not necessarily without an ultimate reward for the society as a whole.